Exploring Intelligence Beyond Language: Neural Structures Unveiled

Written on

Chapter 1: The Essence of Intelligence in Nature

Nature has crafted a diverse array of structures to foster intelligence. This discussion delves into two distinct neural architectures—centralized and distributed—and the complex behaviors that arise from them, which, while devoid of language, exhibit remarkable adaptability.

Language: A Unique Human Trait

Language serves as a defining factor that separates humans from other species. It allows for the creation of countless sound combinations, enabling us to articulate and share our thoughts. In contrast, animal communication is limited to a few specific calls, often tied to immediate external stimuli. For instance, a monkey's cry might signal a threat, hunger, or social dynamics.

At some stage in our evolutionary journey, we internalized language, which enhanced our ability to organize thoughts and develop intricate mental frameworks. This internal dialogue facilitates logical reasoning, scientific inquiry, and the construction of complex systems. All evidence suggests that language—both spoken and internal—is distinctly human.

Historically, many philosophers and psychologists maintained that language and thought are inherently linked, asserting that without language, thought is impossible. Influential figures like René Descartes and John Locke suggested that animals operate solely on instinct, lacking any capacity for abstract thought. However, recent research has demonstrated that animals exhibit complex cognitive processes, learning and adapting behaviors when necessary.

Understanding animal cognition can shed light on the evolution of human thought. However, tracing our evolutionary roots does not imply we have uncovered all aspects of intelligence; human intelligence represents merely one of countless possibilities in the biological realm.

Centralized Intelligence: Insights from Primitive Cultures

While the intricacies of animal thought remain elusive, their behaviors offer valuable insights. Observing how species adapt and solve problems provides a window into their intelligence. For instance, macaques—our close relatives—possess a brain structure similar to ours, characterized by a centralized processing unit. However, their communication methods are limited, yet they demonstrate problem-solving skills.

Researchers have been observing a troop of wild macaques on Koshima Island, Japan. In 1953, they documented a young female macaque named Imo engaging in an unusual behavior: washing her sweet potato in water to remove sand before consumption. Though not inherently fond of water, this young macaque discovered a method to utilize it for food preparation. Her innovative behavior was eventually adopted by her family and later by the entire troop, showcasing a learned behavior rather than an instinctual one.

This trend illustrates how monkeys can develop and pass on complex behaviors that reflect cultural evolution. Although they lack the ability to read or create art, they exhibit regionally distinct behaviors that are shared through observation rather than genetic inheritance. The behaviors initiated by Imo continue to be practiced by subsequent generations of macaques.

In comparison, chimpanzees display even more advanced behaviors, such as tool use and social interaction, which vary significantly across different populations. This variability is not merely a response to environmental factors; it stems from their sophisticated reasoning capabilities.

Humans, chimpanzees, and macaques share a relatively recent common ancestor, suggesting a gradual evolution of cognitive abilities. To understand intelligence in its entirety, we must also explore organisms that possess entirely different neural structures and functionalities.

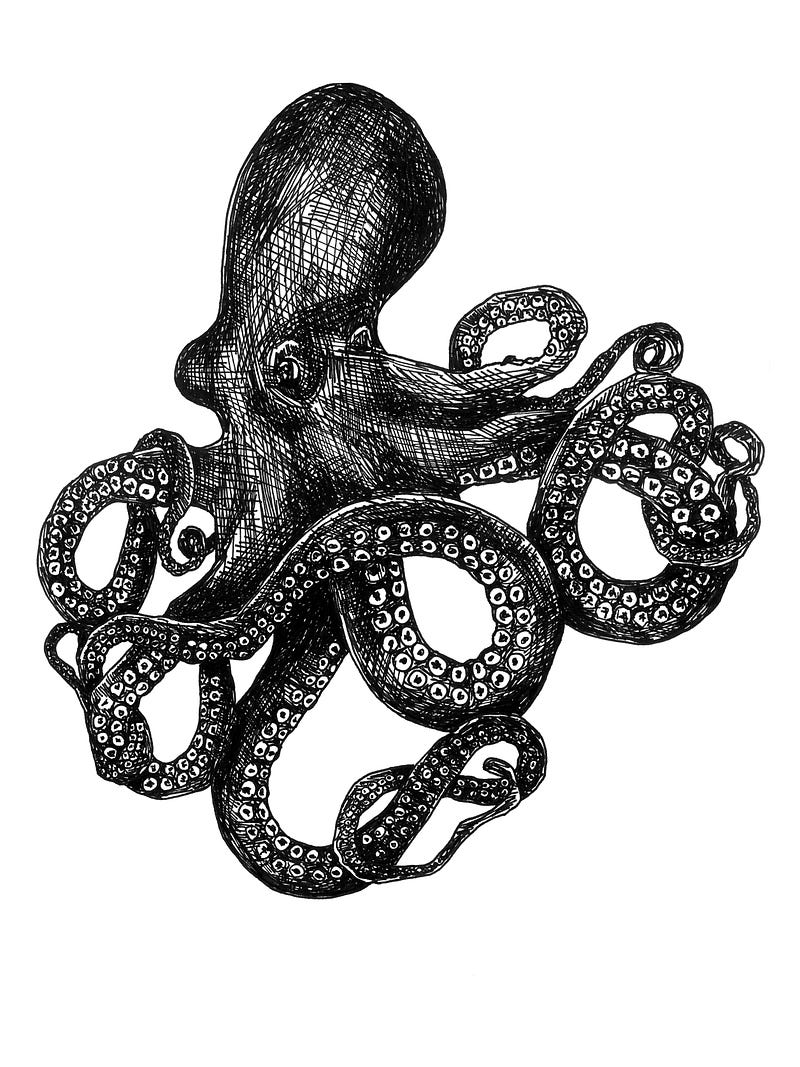

Distributed Intelligence: The Eerie World of the Octopus

The octopus, with its unique physiology, presents a fascinating example of distributed intelligence. With three hearts, blue-green blood, and eight flexible tentacles, it appears almost extraterrestrial. Its evolutionary journey traces back to a primitive flatworm that survived significant genetic mutations, eventually leading to the emergence of the octopus as a highly intelligent invertebrate.

Unlike vertebrates, which possess a centralized brain, the octopus has a distributed neural structure. About two-thirds of its neurons reside in its arms, allowing for a form of intelligence that operates across its body rather than from a single control center. This unique arrangement facilitates semi-autonomous movement, enabling the octopus to coordinate its limbs gracefully.

The octopus demonstrates remarkable intelligence through its curiosity and problem-solving abilities. It has been observed manipulating objects playfully and successfully tackling challenges that confound even adult humans. For example, octopuses in Indonesia have been seen using coconut shells as tools to create shelters, showcasing foresight and innovative behavior.

Contrasting Forms of Intelligence

The octopus and non-human primates provide contrasting models of non-verbal cognition: one embodies a distributed neural structure, while the other features a centralized approach. Despite their differences, both exhibit shared traits in their interactions with the environment. They explore various problem-solving strategies, anticipate outcomes, and engage in playful behavior.

Language serves as a vital interface for humans, organizing neural signals into coherent thoughts. Interestingly, complex behaviors can emerge without the need for language. Varied neural architectures can yield similar intelligent solutions, illustrating nature's ingenuity in developing intelligence in multiple forms. With our linguistic capabilities and abstract reasoning, we may one day create energy-efficient intelligent machines that mirror the diversity found in nature. Or perhaps, in a few million years, an articulate octopus will solve that puzzle for us.